The 2022 Land Gap Report

About the Report

The growing push for climate mitigation has given rise to a new urgency around land use. Countries making ‘net zero’ pledges make up the vast majority of global greenhouse gas emissions. Additional ‘net zero’ pledges are coming from non-state actors, especially the private sector. These pledges usually rely on land-based carbon dioxide removals which are then used to offset a theoretical equivalent amount of fossil fuel emissions in national greenhouse gas inventories.

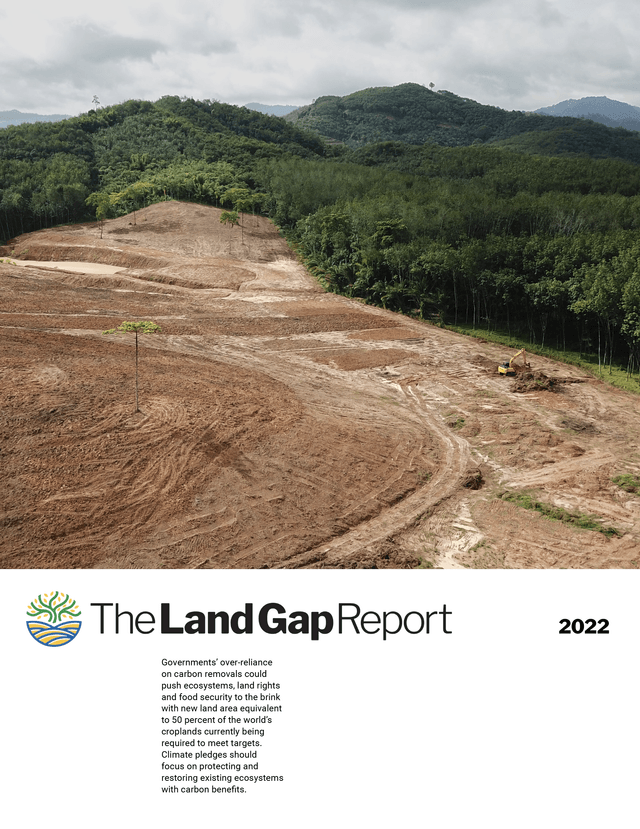

This momentum raises serious concerns if the mitigation burden is shifted away from reducing fossil fuel emissions and onto land, local communities and ecosystems.

This Land Gap Report shows how countries’ climate plans, if implemented, will increase the aggregate demands made on land. The report quantifies the aggregate demand for land and land-use change to address climate mitigation in the climate pledges submitted by Parties to the UNFCCC. A key finding is that countries’ climate pledges assume that almost 1.2 billion hectares of land can be prioritized for carbon dioxide removal.

This land area is larger than the USA and almost four times the size of India.

How did we calculate this? See Land Gap Report methods.

Even more concerning is that roughly half the land pledged for climate mitigation (633 million hectares) requires a land-use change, mostly through plantations and other tree-growing schemes. This could compromise the rights and livelihoods of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

Also, carbon removals by these plantations and new forests just don’t contribute much to limiting warming, or allow for earlier peaking of the global temperatures expected in the coming decades.

The other half of the pledges by area (551 million hectares) is for restoring degraded land or allowing degraded forests to fully regenerate. Maintaining and augmenting carbon stocks in existing ecosystems holds more promise for climate and biodiversity while posing fewer threats to other dimensions of sustainability.

But the potential area available for expanding forest cover is uncertain. It depends on how restoration is conducted – whether it observes principles of ecology and human rights. ‘

These findings have implications for governments’ approach to land-based climate mitigation objectives, including carbon accounting, as well as for biodiversity preservation, and the rights and livelihoods of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPs and LCs).

Download individual chapters

Readers have requested individual PDFs for the main Chapters in The Land Gap Report. Below, please find downloadable versions of the Chapters. These are unmodified from text in the main report.

Key Messages

The Land Gap

- Quantifying the area of land required to achieve carbon removal goals in country climate pledges reveals both an unrealistic expectation for land-use change and an encouraging focus on restoring and regenerating degraded lands.

- Increased reliance on land for carbon dioxide removal increases the risk of overshooting warming thresholds and of dangerous climate impacts. The legitimacy of net zero climate goals is dependent on rapid decarbonization rather than over-relying on removals, particularly from land.

- Increased demand for land as a ‘carbon sink’ exacerbates land conflicts and food insecurity, escalating climate injustice by framing land for its carbon removal potential, since land has multiple uses.

Forest ecosystem protection and restoration

- Primary forest protection and restoration is the most effective climate mitigation action in the land sector, providing co-benefits for adaptation, biodiversity conservation and other critical ecosystem services.

- Primary forests and the ecosystem services they provide are irreplaceable and cannot be offset through new plantings.

- Forest management should be informed by a comprehensive evaluation of all ecosystem services, and through respecting the rights and traditional knowledges of indigenous peoples and local communities.

- Carbon accounting rules need to be modified to recognize the carbon retention value of forest ecosystems and their ecosystem integrity.

- Appropriate decision-making processes, policies and financial incentives are needed to facilitate indigenous peoples and local communities, landowners and governments in maintaining primary forests and improving the conservation management of landscapes, including through buffer zones and reconnecting remnant primary forest areas.

Land rights of indigenous peoples and local communities

- With few exceptions, the various national climate mitigation pledges have paid little attention to who, in practice, is living on, using and managing the lands involved, much less to existing land rights of indigenous peoples and local communities.

- Without an understanding of history and power relations shaping the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities to land and territories, and thus without a social justice lens, any attempt to fulfil the many land-based climate pledges is likely to perpetuate injustices.

- The most effective and just way forward is to ensure that indigenous peoples and local communities have legitimate and effective ownership and control of their land. They must also have a strong voice to self-represent and engage on equal terms – ultimately exercising self-determination in the search for sustainable pathways for use of their lands and territories.

Agroecology for socioecological resilience

- Business-as-usual in agriculture and food systems is not an option. Transformative change is urgently needed to move away from emissions-intensive industrial agriculture.

- Alternatives based on biologically diverse systems can contribute to both climate adaptation and mitigation. Agroecology provides these and other multifunctional benefits centred on ecological and social resilience that is achieved through the sustainable management of biodiversity.

- Agroecology contributes to the realization of various human rights. Human rights-based approaches help to address climate change challenges and biodiversity loss, while strengthening the agency of right-holders such as indigenous peoples, peasants and women.

- Key policy actions are needed to foster the restoration and sustainable use of agricultural biodiversity by elevating agroecology as a means to practice biologically diverse agriculture, a key holistic approach for climate change adaptation and mitigation.